Gregory Laxer

In school, we were told that we lived in a great nation, a democracy. We were taught about the sacrifices made to wrest control of this land from the British Crown, and of the brilliant minds assembled in Philadelphia to hammer out the details of how we were to govern ourselves.

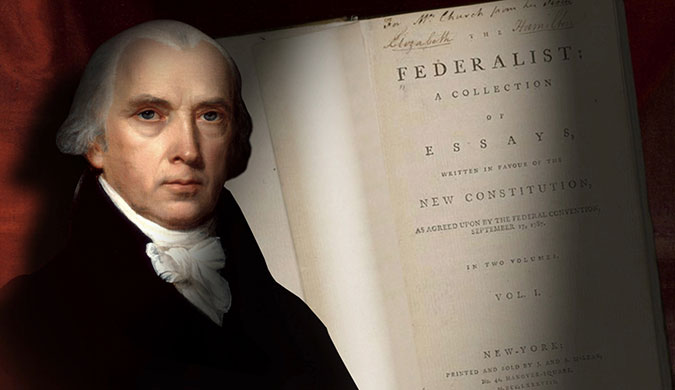

I can’t recall if the Federalist Papers were discussed in any detail, though. And so it was most interesting just recently to finally read the slim paperback I bought many years ago for 44 cents. The Federalist Papers (Pocket Books, 7th Printing, 1976) contains 26 of 85 essays penned by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay. The articles were published in leading newspapers, 1787 to 1788, under the collective pseudonym “Publius.”

These Founding Fathers underlined what they felt were flaws and shortcomings in the proposed Constitution being cobbled together to succeed the Articles of Confederation, the original document for governance in the wake of the War for Independence. They believed that a strong national government, as opposed to a mere confederation of the individual states, was essential to guide the original 13 colonies as “manifest destiny” would inevitably vastly increase the territorial area of the new nation, the full extent of which they weren’t even aware.

I’m sure that many of us who complain about what we perceive as dwindling respect for our democratic rights have encountered some smart aleck who immediately replies: “This isn’t a democracy, it’s a republic.” What does this actually mean?

Fortunately, James Madison explained it brilliantly in Paper Number 10, “Factions: Their Cause and Control.” There is a discussion of the problems generated by a particular segment of society gaining undue dominance over the others, and make no mistake: the authors recognized that they lived in a class society, and they themselves represented the wealthy elite of the time.

Democracy means “direct rule by the people [‘demos,’ from the Greek].” But perhaps the only real democracy was the ancient city-state of Athens, where citizens came together at the agora to discuss and debate the pressing issues of the day. Madison points out that the original 13 colonies were already too unwieldy in territory to permit a direct rule by the people, assembled together. Imagine the impracticality of trying to govern the nation by direct rule in the future, when the territories farther west were settled. And so, the need for a republic: a system wherein the citizenry elects locals to represent them in assemblies (legislatures) at a central seat of government at some distance removed, there to decide the course of the nation.

A large republic is preferable to a small, Madison writes, because with more electors “[I]t will be more difficult for unworthy candidates to practice with success the vicious arts, by which elections are too often carried; and the suffrages of the people being more free, will be more likely to center in men who possess the most attractive merit, and the most diffusive and established characters.”

I think we must hold Madison blameless for not foreseeing the rise to the presidency of an inimitable “character” like Donald J. Trump. But throughout the Federalist Papers, the authors exhibit a keen awareness of the threat to national unity posed by internal divisions, insurrections (“Shays’ Rebellion” in New England was a very recent event) and above all, a “confederacy” among several of the states to rebel against the central power. Thus, as Abraham Lincoln would proclaim seven decades later when the Civil War erupted: “The union must be preserved at all costs.”

In Paper Number 11, “Union and Economic Growth,” Hamilton complains of the smug superiority exhibited by the European powers that had established empires: “The superiority she [Europe] has long maintained, has tempted her to plume herself as the mistress of the world, and to consider the rest of mankind as created for her benefit. Men (…) have attributed to her inhabitants a physical superiority…” How marvellous the irony that the USA now proclaims itself “the exceptional, the indispensable nation,” spreading its military tentacles over the whole globe.

In Number 14, “The Virtues of Bigness,” James Madison even hints that empire may yet be the destiny of the newly established nation, so rich in natural resources.

In Number 34, on taxation, Hamilton asserts that the military is needed to defend commerce, and that it would be “absurd” (verbatim) to renounce offensive war on principle. Quite a heaping dose of pragmatism! But he almost tips the scales back in his favor in Number 21, “The Enforcement of National Law”: “The natural cure for an ill administration, in a popular or representative constitution, is a change of men” [emphasis added]. Are you paying attention, Mr. Trump?

The Founders would undoubtedly be horrified at what’s become of the United States. Police departments from coast to coast are now armed with lethal military gear, and they don’t hesitate to employ it. Interestingly, Hamilton argued against a need to enumerate a Bill of Rights, but such was soon incorporated into the Constitution. But the right of young male African-Americans “to be secure in their persons” (4th Amendment) is obliterated by police bullets regularly. Our legislatures are chock full of, not wise, selfless, meritorious individuals, but creatures kept on short leashes by corporate lobbyists. Every few years, we get to re-elect, or replace, these incumbents. Does this constitute democracy? Don’t the citizens of the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea exercise the same right? I could easily argue that the representatives elected to their National Congress are more genuinely patriotic than America’s.

In Paper Number 39, “Republicanism and Federalism,” Madison again defines a republic. He reminds us government derives its power from the people, the consent thereof. And I now ask: what recourse save revolution is available when government has become utterly corrupted?

Just a little note “for posterity”: Because of the limitation on length of material posted here, I intentionally avoided the “rather major” issues of the fate of the indigenous people on this continent, the issue of chattel slavery, and who was deemed a citizen entitled to cast a vote (“Women need not apply!”). Finally, I note that the Oath of Office for Executive Branch positions neither requires the presence of a bible, nor swearing “so help me God.” “Affirming” allegiance to one’s duties is more than adequate.

Great editorial. However, I must quibble with the explanation given in response to “some smart aleck who immediately replies: ‘This isn’t a democracy, it’s a republic.'”

Madison and the Founders recognized the pure form of democracy where all citizens vote – i.e. direct democracy – was logistically impossible. But, they did implement another form – i.e. representative democracy.

A republic is defined as a nation governed by the rule of law as opposed to the arbitrary decrees of authoritarian rule – in this case, the British monarchy.

Therefore, the U.S. was established as a federal presidential constitutional republic based on representative democracy.

BTW, Athenian democracy wasn’t pure either. Only adult male citizens could vote, and this excluded most of the population – e.g. women and slaves.

Thank you for your comment. I took my definition of a republic directly from Madison in the Papers. He only discussed the concept of the citizens being represented, via elected delegates, in the governance of the nation. He makes no use of the phrase “rule of law.” But of course the rebellion against the British Crown was a reaction to the notion that a mere mortal, claiming to have the full backing of the Almighty, can arbitrarily dictate how things run in the colonies. But that statement, too, needs qualification, as the Brits already had a legislative body (Parliament) with input into national policy. And though to this day, if I’m not mistaken, the UK has no formal constitution, they already had a Bill of Rights in place at the time the Founders were discussing the best way to govern the newly declared United States of America. Hamilton’s position was that adequate protection of citizens’ rights was already built into the Constitution and did not require a separate, or additional, document to spell these out. “The rule of law” has become a very popular notion bandied about here in the States and, in my view, is usually employed to try to divert our attention from the fact that “the game” is so frightfully rigged in favor of the uber-rich, against the interests of “the little guy.”

The U.K. Parliament and parliamentary elections did not come into being until 1801 with the Acts of Union 1800. So, it was the King who arbitrarily exercised power at the time of the American Revolution. Today, it is the Prime Minister – as Head of Government – who holds power. Officially, the U.K. is a unitary parliamentary

constitutional monarchy having an “unwritten” constitution based on various texts and common law.

Wikipedia defines a republic as:

Seems odd that England would have had a Bill of Rights in place before a Parliament. Okay, hold the phone! I just checked Wikipedia and of course England had Parliament long before the 19th Century! The English Bill of Rights was established by an Act of Parliament in 1689. The date of 1801 you have cited is considered the birth of their Parliament as currently set up, and the current iteration is only the 57th such sitting. A “constitutional republic” or “representative democracy” is indeed what the Founding Fathers sought to establish here. The problem we face in modern times is that under the Rule of Law, to borrow from Orwell, “…some of us are more equal than others.” And the Members of Congress have (to a great extent–I’m feeling charitable) morphed into the representatives of corporate interests (remember when ‘Scoop’ Jackson, of Washington State, was known as ‘The Senator from Boeing’?), and they have surrendered the right to declare war to the Executive Branch through cute little semantics games. Obviously I could go on and on with my grievances against the Established Order, but why bother? Anyone not wearing really effective blinders can look at the current state of the USA and not be happy with the view.

Agreed. My point was simply to help explain the reasons why America’s Founding Fathers established a republic and representative democracy in opposition to the arbitrary rule of the British monarchy, and to refute the notion often made by right-wingers (who love arbitrary power if they are the ones who hold it) that a republic is incompatible with democracy.

Republic. Democracy. The question devolves to “What do we mean by ‘democratic rights’ in contemporary US society?” Slavery is still legal for prison inmates. The very elemental right to cast a vote in free, open elections had to be won by blood for racial minorities within the lifespans of many of us who post comments here. And now Georgia, among other locales, is trying to bar tens of thousands of voters from the polling place. Should a convicted felon be barred from voting FOR LIFE?? The right to a fair trial is kind of irrelevant when you’re cut down in a hail of police bullets. Many, many problems here in “The Greatest Nation Ever,” and no solutions in sight from the two wings of The Party of Property.

With regards to the opening paragraph, British America was only about half of the current landmass of the USA Today. Are you also taught about how you got the other half?

Alex–As I indicated, the “westward expansion” was beyond the scope of what I could address. I write as someone who was in elementary school (not sure what it’s called where you live, which I’m guessing is the UK) in the 1950s. Suffice it to say, the cultural environment was the one in which “cowboys” were the Good Guys and “Injuns” were the Bad Guys. Exceptions to this were very rare, e.g. an occasional episode of “Have Gun Will Travel.” That show even featured an episode where ‘Paladin’ comes to the aid of Chinese immigrants being excessively exploited in a mining operation. I think Richard Boone was a very under-appreciated actor!

I think cowboys and “Injuns” was played innocently enough by generations of children who grew up on a diet of thrilling westerns. I wonder what it has been replaced by?

I was also drawn by your last paragraph (I assure you I read everything in between) which seems an increasingly logical conclusion.

“…played innocently…” Well, yes. Young minds soak up the culture of the environment in which they’re raised. But autodidactic “deprogramming” is possible. By the time I was a member of the very same organization that was used to exterminate so many Native Americans I had firmly concluded that the John Wayne Mentality (oxymoron!) was utterly wrong. “The Green Berets”! OMG, what an awful movie!! As I type this, Americans are choosing (well, some are struggling desperately in places like Georgia to participate) the Congress that will be seated in January. Media consensus is that the Democrats have little to no chance of regaining the majority in the Senate. At least if they (note that I don’t say “we”) win the House, some degree of “check” on Trump is possible. The Dems have been moving more and more to the right past few decades. Slight indeed will be any toast I might raise to their possible electoral wins today.